New Regulations to Monitor Forever Chemicals in the Environment

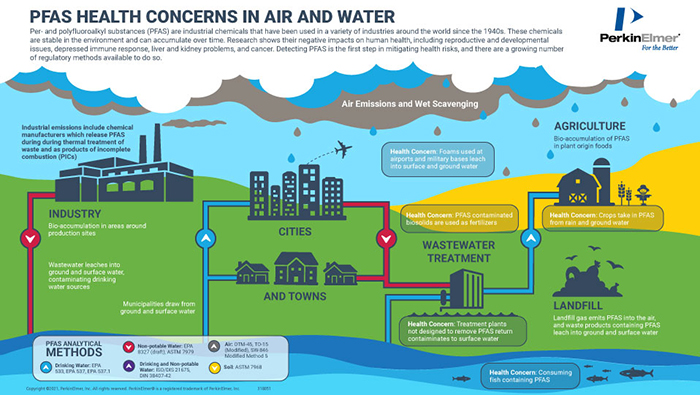

Since their development in the 1940s, PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) have been utilized in industrial applications due to their chemical stability, thermal stability, and high resistance to degradation. PFAS chemicals have been named “forever chemicals,” because they are extremely persistent, lasting thousands of years. Significant attention has placed PFAS as a rapidly emerging environmental and safety threat in the United States. PFAS are generally released during thermal treatment of waste and products of incomplete combustion and can be found in a variety of products including fire extinguishing foams, food packaging, non-stick cookware, cosmetics, and cleaning supplies. The bioaccumulation of PFAS occur at production sites and landfills, both of which acting as the primary locations for PFAS leaching into ground and surface water. This PFAS contamination makes its way into the water supply that is often used for human consumption and agricultural applications. Without the appropriate measures to remove the contaminated particles, many water treatment facilities remain vulnerable to PFAS contamination.

Adding to the issue is the vast number of existing PFAS, with nearly 7,000 PFAS related compounds currently recognized, and more PFAS derivative compounds expected in the future. As a result, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has created an action plan to address PFAS contamination in drinking water. Regulations, such as the fifth Unregulated Contamination Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5), are critical to detection and treatment efforts since public water systems require analysis of PFAS, with nearly 10,000 water systems in need of analysis. The sampling period ends in 2025, where sampling data is to be collected and analyzed for 2026 review. Let’s take a look at the PFAS developments in UCMR 5 and the future of PFAS regulation.

3 EPA Directives

The EPA has developed an integrated approach to address the environmental and safety concerns of PFAS, that focuses on improving PFAS contamination and supporting environmental justice.1

- Research

The EPA is considering the lifecycle of PFAS, ensure science-based decision making to define categories of PFAS and methods, investigate sources of contamination and exposure pathways, and better understand how the burden of PFAS pollution impacts communities with environmental justice concerns.

- Restrict

Emphasis is placed on prevention of PFAS from entering the environment, holding polluters accountable using statutory authorities, establish voluntary programs to reduce PFAS emissions and prevent or minimize the impact of PFAS emissions on all communities, regardless of income and race.

- Remediate

With the goal of rapid remediation of PFAS contamination, the EPA will leverage the power from statutory authorizes to maximize the funding and performance of responsible parties, accelerate the execution of treatment and disposal of PFAS, and prioritize the protection of disadvantaged communities through the equitable access of PFAS solutions.

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA)

SDWA has enabled the EPA to require water systems to conduct sampling for unregulated contaminates every five years. In March 2021, the EPA published the Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule advancing new data to improve the EPA’s grasp on the frequency of 29 PFAS compounds found in the nation’s drinking water and, specifically, at which levels. UCMR 5 is expected to expand the number of participating drinking water systems, generating data that will optimize their ability to conduct state and local assessments of contamination.2

Definitions Needed to Understand The 5 Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5)

- Public Water System (PWS): Provides water for human consumption via pipes/other constructed conveyances to at least 15 service connections or serves an average of at least 25 people for 60+ days a year.

- Community water System (CWS): This is a PWS that supplies water to the same population year-round

- Non-transient, Non-community Water Systems (NTNCWS): PWS that supplies water to at least 25 of the same people at least 6 months of the year/not year-round

- Transient, Non-Community System Water System (TNCWS): PWS that supplies water where people do not remain for long periods of time

The UCMR 5 published its final rule on December 27th, 2021. EPA pre-sampling activity will commence in 2022, the sampling period will take place between 2023-2025, and the post-sampling activity will take place 2026. The UCMR 5 Rule states that all large systems (CWSs and NTNCWSs) serving larger than 10,000 people, small systems (CWSs and NTNCWSs) serving 3,300 or more people and 800 randomly selected small systems serving 25-3,300 people are required to collect samples during a 12-month period from January 2023 through December 2025. Future considerations regarding UCMR development include prioritization of additional PFAS for the inclusion of UCMR 6, as improved techniques to measure PFAS are developed and validated.3

Key Changes that have occurred from UCMR 4 to UCMR 5 include:

- Elimination of different requirements based on system size, no monitoring tier list

- Applicability expanded to all CWS/NTNCWS serving 3,300+

- 800 Randomly selected PWSs serving <3,300

- AWIA of 2018: Funding expanded PWS scope for EPA to cover shipping and analytical costs of samples.4

UCMR Sampling Design, Monitoring and Reporting Explained

Sampling Design

This is shared with stakeholders and is peer reviewed, with 800 randomly selected small PWSs (serving less than 3300) notified by 02/22/22. The data quality objectives were outlined as follows:

- Occurrence data for unbiased national exposure estimates

- Representative of both PWS size and source water type

- Population weighted

- At least 2 small systems are selected for each state

Monitoring

The EPA is going to add funding to support all 3300-10,000 ppl PWSs, however, it is currently only covering 8%. The strategy used to assess the monitoring includes determining the national contaminant occurrence, develop a primary tier and scope, utilize available methods and common techniques, and ensure consistency with AWIA provisions.4

Reporting

The Minimum Reporting Limit (MRL) is the minimum quantitation level that, with 95% confidence, can be achieved by analysts at 75% or more of US Labs using a specific method. The EPA establishes MRL using data from multiple labs performing “Lowest Concentration Minimum Reporting Level (LCMRL) studies to identify capability. Each lab lowest concentration MRL (LCMRL) is the lowest true concentration for which future recovery is predicted to fall, with high confidence at 99%, between 50%-150% recovery. The LCMRL is the lowest concentration that specified quality measurements can be made by a lab. The MRL is designed to produce quality and consistency across UCMR labs, while balancing lab capacity.5

UCMR 5 Lab Participation Process and Cost

The process for lab participation in UCMR takes approximately 3-6 months and involves six steps:

- Request to Participate

- Register

- Complete Application

- EPA Review Application

- Proficiency Testing

- Formal Approval by EPA

Key changes made from USMR 4 to USMR 5 for a lab’s participation include:

- When registering, UCMR 4 stated that to participate as a UCMR lab, the lab had to register within 60 days of final rule publication (12/20/16) and application within 120 days. UCMR 5 now states that to participate as a UCMR Lab, registration and application must be completed by 08/01/22. These changes were enacted to provide greater flexibility for interested labs.

- Regarding proficiency testing (PT), EPA plans to offer 3 PT studies prior to 12/27/21 (final rule pub) and 3 PT studies after 12/27/21.

As of Jan 2022, 35 labs have been approved for UCMR 5, with additional PT studies expected to be added. Based on the current funding, the number of small PWSs participating is ~1,200, with a high demand of more approved labs.6

Ensuring Safe Water from Every Tap

HFPO dimer acid and its ammonium salt are also known as “GenX chemicals” because they are the two major chemicals associated with the GenX processing aid technology. GenX is a trade name for a processing aid technology used to make high-performance fluoropolymers without the use of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). The future of PFAS analysis will be greatly influenced by the identification of PFAS categories and final toxicity assessments for GenX and additional PFAS. The EPA has already begun to publish the toxicity assessments GenX chemicals. The goal of the toxicity assessment for GenX is to continue to develop a robust understanding of how these additional PFAS impacts health and the environment. In addition to the GenX PFAS, the Office of Research and Development is also developing toxicity assessments for five other PFAS including PFBA, PFHxA, PFHxS, PFNA, and PFDA.1

The difficulty in gathering information on PFAS is primarily due to the large size and diversity in this class of compounds. In response to the large number of PFAS currently in use, the EPA is planning on classifying the PFAS compounds into smaller categories. These categories will be based on parameters such as chemical structure, physical and chemical properties, and toxicological properties.2 The EPA has outlined two approaches to categorize PFAS. The first is utilizing toxicity and toxicokinetic data to develop PFAS categories for further hazard assessment and to inform hazard or risk-based decisions. The other approach involves developing PFAS categories based on removal technologies using existing understanding of treatment, remediation, destruction, disposal, control, and mitigation principles. These approaches will function to identify missing elements in the EPA’s understanding of PFAS from hazard assessments and removal technology perspectives, further assisting the EPA’s prioritization for future actions. Additionally, the EPA is going to develop a PFAS categorization database that will capture key characteristics of individual PFAS, including category assignments.1

As the EPA continues to expand its understanding and actions to PFAS contamination, robust regulations become even more relevant. Directives from UCMR 5 offer the necessary regulatory frameworks to enhance scientist’s understanding of PFAS on the environment and human safety. Additionally, UCMR 5 empowers authorities to enforce restrictions and prevent further contaminations. For more information on PFAS, see PerkinElmer’s PFAS Brochure.

References:

- US EPA. “PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA’s Commitments to Action 2021—2024”. October 2021, https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-10/pfas-roadmap_final-508.pdf.

- US EPA. “Safe Drinking Water Information”. 14 July 2015, epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/safe-drinking-water-information.

- US EPA. “Ground Water and Drinking Water”. 25 June 2019, www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water.

- US EPA, OW. “Monitoring Unregulated Contaminants in Drinking Water”. www.epa.gov, 3 Aug. 2015, www.epa.gov/dwucmr.

- US EPA, OW. “Reporting Requirements for the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule UCMR 5”. www.epa.gov, 1 Sept. 2015, www.epa.gov/dwucmr/reporting-requirements-unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule-ucmr-5.

- US EPA. “Laboratory Approval Program for the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5)”. www.epa.gov, 1 Sept. 2015, epa.gov/dwucmr/laboratory-approval-program-unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule-ucmr-5.